Post-Concert Musings: My Journey with Beethoven (so far)

- lianabranscome

- Mar 5, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Mar 6, 2025

Beethoven’s famous quote, “Music is the mediator between the sensual and the spiritual life,” has been on my mind a lot these past couple years and it’s only recently that I am beginning to discover what he might have meant by that. I’ve featured these words on my quartet’s website, recited it to audiences in pre-concert talks and paraphrased his words in post-concert receptions as I try to impress my audience members (haha!). But experiencing the true meaning of these words has been more of an ongoing excavation.

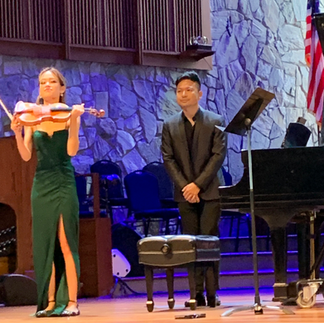

From September to November 2024, I played five all-Beethoven recitals with my wonderful pianist and collaborator, Beiyao Ji, featuring the first, fifth and seventh sonatas for violin and piano. I wanted these concerts to bring people together and to showcase a slightly different side of Beethoven. I paired these iconic works with lesser-known anecdotes from his life that would show us a Beethoven unseen by the public and misunderstood by those around him.

This was a guy who loved a good joke or a pint of beer with friends. Beethoven’s Sonata No. 1 for Violin and Piano in D Major, Op. 12, No. 1 is a good example of this. It was written during a happy period in his life and he was just one year older than me when he wrote it. You can hear the joyful exuberance of youth and optimism as well as a kind of curiosity about life. Beethoven was forced to drop out of school at age 11 in order to support his family and never learned how to divide or multiply. However he sought knowledge all his life and loved to explore the world, as evinced by his extensive library which contained numerous books on literature, science and nature.

A life-long lover of nature, Beethoven used to wander in the fields, air-conducting as he heard symphonies in his head. In fact, he once caused a herd of oxen to stampede because he waved his arms so wildly. He was also a wanderer, often losing track of time. Once, he wandered so far that he became lost and began looking into people’s windows in search of directions (and food!). Alarmed at the disheveled stranger peering into their windows, the townspeople sought the local constable who escorted Beethoven to jail. Despite Beethoven’s fervent protests that he was Beethoven and needed to be released immediately, the well-meaning constable smiled and chalked it up to delusion. You can imagine the constable’s horror the next morning upon finding out the “madman” he’d arrested really was Beethoven. Beethoven found more than adventure and solace in nature: he also found God. Beethoven once remarked that it seemed to him that each leaf and animal cried out: Holy, Holy!

Beethoven looked to God to fill the silence that became more profound with each passing day as his deafness became a reality. He approached God in an extremely human way. It was conversation with God that he prioritized, not the liturgical aspect of faith. Some of Beethoven’s most significant conversations with God took place in nature. This love of both nature and faith is on full display in his Spring Sonata, the opening melody conjuring feelings of gratitude and adoration. Spring meant something different in Beethoven’s day, where winter was a more formidable beast than the one we know today with our in-home electricity and central heating. Survival was not guaranteed. Spring meant that you had made it through the storm. In a way, the Spring Sonata is a prayer of thanksgiving.

With the advent of his deafness, Beethoven was the least affected when he composed: he heard the notes in his mind. He suffered the most in conversation and it was because of this that he became the antisocial, scowling figure that we see in his portraits. While Beethoven maintains his reputation as a recluse and a misanthrope, much of his isolation was against his will. Forced to communicate via a notebook, Beethoven lost the natural ebb and flow of the conversations he loved so much. He felt himself increasingly disqualified from passing casual time with his fellow man and it grieved him deeply. He expressed a strong desire that his body and illness be studied after his death so that “as far as possible, at least the world will be reconciled to me after my death.” He wanted us to know that he hadn’t willfully shut himself away from the world. In 2024, scientists answered Beethoven’s plea. An analysis of strands of Beethoven’s hair revealed that in addition to various other serious ailments, he suffered from an unprecedented degree of lead poisoning which almost certainly contributed to his deafness as well as the liver and kidney afflictions that later took his life. It is nearly certain that he suffered debilitating stomach pains every day of his life.

What is a sonata if not a conversation? Journeying through the sonatas granted us an opportunity to share music and humanity with a lot of different audiences. One of our first performances of the program took place at Professor Kevin Kenner’s home near the University of Miami. Sharing this music in the setting of a home made me grateful for what Beethoven held so dear, the community and warmth of a hearth. We also took the program to a local school, several churches and concert series. I had the opportunity to play the program while in a variety of different states of health myself, causing me to admire Beethoven all the more for continuing to give while his physical body failed him.

For one of the concerts, we featured the wonderful tenor Jay Arnn and pianist David Block in a performance of two of Beethoven’s songs: Adelaide, Op. 46 and An die fern Geliebte, Op. 98. These songs offer an inside look into the state of Beethoven’s love life. A notorious romantic who proposed and was rejected (in public!) to three different women, Beethoven never gave up on love, though he never married. As it says in An die fern Geliebte:

Ah, you cannot see the longing,

Which is burning in my eyes,

And my sighs are widely scattered

In the space that between us lies.

Beethoven kept yearning after unattainable women who were often already married, of a much higher societal class or were his own students! One of his most famous letters, to his Immortal Beloved, expresses an outpouring of emotion and love in the face of some unknown immutable obstacle. While we don’t know the identity of the Immortal Beloved (or if the letter was ever sent), one can’t help but be moved by the outpouring of Beethoven’s devotion:

“While still in bed my thoughts rush toward you my Immortal Beloved now and then happy, then again sad, awaiting fate, if it will grant us a favorable hearing - I can only live either wholly with you or not at all. Yes, I have resolved to wander about in the distance, until I can fly into your arms . . .”

As to the recipient of this letter, it’s been speculated that one Baroness Dorothea von Ertmann may have been a possible contender. An accomplished pianist in her own right, the baroness studied under Beethoven shortly after arriving in Vienna with her husband, Austrian military officer Stephan Leopold Freiherr von Ertmann. Though there’s scant evidence to back up the contention that Dorothea was the Immortal Beloved, the relationship between teacher and pupil was unusually profound and within their history there is a touching story. In March of 1804, Dorothea and Stephan lost their only child, their three-year-old son, Franz Carl. Dorothea was unable to shed tears at the funeral and instead sent for Beethoven. The great man had no words for the baroness. Instead he took her hand and led her to the piano where he played for her for hours, playing whatever came into his heart. Dorothea later said, “he told me everything with his music and at last brought me comfort.” Years later, Beethoven dedicated his Piano Sonata No. 28 in A Major, Op. 101 to her, the first of his late piano sonatas. Whenever I doubt in the power of music to heal, I remember this story. This is the reason I put my whole heart into every concert, no matter how large or small the crowd: we never know who might need the healing power of music.

Beethoven’s magnanimity was far reaching. When he received word that J.S. Bach’s youngest daughter, Regina Susanna, had fallen on hard times, he set about raising money for her livelihood, donating the proceeds from the premiere of his Eroica Symphony so that she might live more comfortably.

It’s jarring to realize that Beethoven’s Sonata No. 7 in C minor was written just a few short, harrowing years after his cheery D Major. In just a short timespan, Beethoven’s deafness and increasing physical ailments had become a dangerous reality. C minor, the key of his Fifth Symphony and the signature of fate’s knock, signals this dark reality. Yet even in this storm, there are hopeful and assuring melodies. I see this as Beethoven’s testament: even in the darkness, there is a pathway to light.

So what do I think the quote “Music is the mediator between the sensual and the spiritual life” really means? I’m sure I’ll keep uncovering more layers to that answer the longer I keep making music and connecting with people. I think for Beethoven, spirituality was not about being pious or living what one might call a “religious life.” Spirituality was for the common man, the person facing tribulations, the outcast, the person clinging to hope. I think Beethoven wanted to show us, through his music, that no one was too far gone to experience spirituality. I think Beethoven wanted to point us to the light.

Comments